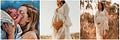

Momfluencers: Getting Paid to Post About Motherhood Online

Sara Petersen on the performance of motherhood across social media—while the actual labor of mothering remains hidden.

Despite the beautiful, picture-perfect moments of motherhood captured on Instagram, the actual act of mothering is, in fact, extremely hard work.

When I'm pushing a stroller up a hill, sweating profusely while carrying the crying child who refuses to sit, when I’m wrestling a car seat into a rental car after 14 hours of travel, all I can do is rein in m…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Startup Parent with Sarah K Peck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.